Dutch Subsidy Landscape By Olivier de Jonge

The Role of Subsidies in the Netherlands

.png?width=473&height=410&name=solar-electricity-per-capita%20(1).png)

Introduction

In 2018, the Netherlands generated over 80% of its electricity from fossil fuels, making it one of Europe’s laggards in the energy transition. Seven years later, the Netherlands is a global frontrunner. With over half of all electricity generated by renewables, the Netherlands has two times the solar energy per capita and 1.6 times the wind energy per capita versus the European average. According to the national grid operator (Tennet), much of the national congestion issues now faced by the grid, can be attributed to the faster-than-expected rollout of renewables (after the outbreak of the Ukraine war).

Subsidies have played a crucial part in the rollout of renewables. In 2023, the Netherlands behind Portugal had the second-most subsidy schemes for renewable electricity in Europe (at 73). This significant government support has played a major role in accelerating the rollout of renewables in the country, making the SDE++ scheme especially influential.

However, grid congestion is rapidly emerging as the key constraint. In 2025, more than 12,000 companies are waiting for new or expanded grid connections, leading to delays in project implementations and impacting the effective use of subsidies. Subsidy budgets for renewable electricity production have already been halved due to grid limitations, indicating that future schemes are likely to focus more on flexibility, storage, and grid-supportive solutions rather than just generation.

These changes reflect a broader trend in the Dutch and wider EU subsidy landscape, as renewables, due to their low marginal cost, regularly price fossil generation out of the merit order. Once built, renewable plants bid at near-zero marginal cost, but further growth depends increasingly on addressing grid infrastructure bottlenecks.

Current Subsidy Landscape in the Netherlands

This white paper will discuss the primary means to subsidize IPPs, through the Subsidie Stimulering Duurzame Energie (SDE). So far, there have been three principal schemes: SDE (2008-2012), SDE+ (2012-2020), SDE++ (2020-present). The SDE intends to subsidize the production of renewable energy and C02 reducing technologies. Through an application process, participants can receive subsidies over a period of 12 to 15 years. Its status remains uncertain; for several years, the scheme has been provisionally extended, but successive government officials responsible for it have repeatedly indicated that it will be replaced.

SDE Compensation

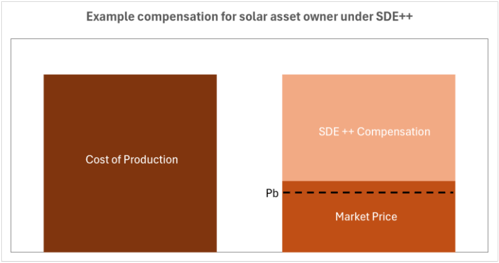

The SDE++ employs a one-sided contract for difference (CfD) scheme. Essentially, the SDE++ compensates producers so that they receive, at least, the ‘production cost’ of that electricity. The ‘production cost’ of electricity is determined through a bidding process whereby producers bid for the lowest subsidy (per ton of C02 avoided) needed to realize their project (ie. Levelized Cost of Electricity), and these biddings are ranked with the least expensive options used first until the subsidy budget has been depleted. Compensation is limited to a baseline price, below this price (Pb), compensation is capped. Figure 1 displays a situation whereby the market price is above the baseline price, and an asset owner is compensated for the remaining marginal loss.

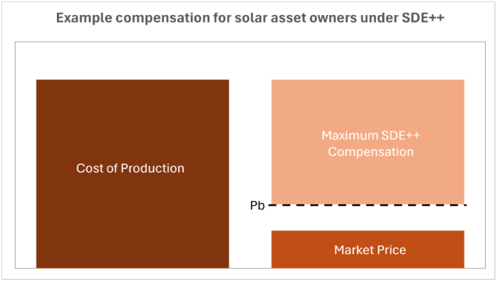

Figure 2 displays the situation whereby the Market Price falls below the baseline price. Here compensation is capped, and the marginal cost of production remains larger than the total compensation.

These two situations illustrate how the basic SDE compensation mechanism works, demonstrating how they (partially) protect IPPs from market conditions.

The SDE subsidy scheme has played a pivotal role in supporting the development of renewable energy and CO₂-reducing technologies in the Netherlands. While its future remains uncertain, the current SDE++ scheme continues to provide targeted financial support through a competitive bidding process. By compensating producers based on avoided CO₂ emissions and maintaining a capped baseline price, the SDE++ ensures that public funds are allocated efficiently, though it also introduces limitations when market prices fall below the baseline.

SDE Developments

Several developments in the SDE are relevant to IPPs and the subsidy landscape in the Netherlands.

Changing compensation for negative-price hours.

Recent variations of the SDE have reduced the amount of compensation for negative-price hours in the Day-ahead market. This, paired with the increase in prevalence of negative-price hours in the Day-ahead market, means that IPPs are receiving significantly less subsidy. The timeline for negative-price hour compensation is:

The reduction in compensation during negative-price hours on the Day-Ahead market poses a significant commercial challenge for IPPs. Due to the large roll-out of solar in the Netherlands, hours where solar production peaks are also the hours in which prices on the day-ahead market are most likely to be negative. This is reflected in the low capture price for solar (the actual average revenue that producers receive which is driven by the prices in hours where production peaks).

Changes SDE 2026

The current revision of the SDE 2026 includes several changes relevant for wind and solar IPPs:

End of SDE.

2025 was initially expected to be the final year for IPPs to apply for subsidies under the SDE++ scheme. However, the Dutch government has now confirmed that the scheme will continue in 2026, with a provisional budget of €8 billion. This means IPPs will still be able to apply for support next year. In the longer term, the government plans to shift toward a two-way Contracts for Difference (CfDs) as the main subsidy model, better aligning with the EU energy market directive.

Understanding CfDs and their effects on IPPs

The SDE++ scheme is expected to be replaced by a new subsidy mechanism in the coming years. The new scheme will be better aligned with the EU Electricity Market Design Directive, which recommends the use of two-way Contracts for Difference (CfDs) as the preferred form of state aid for renewable electricity generation.

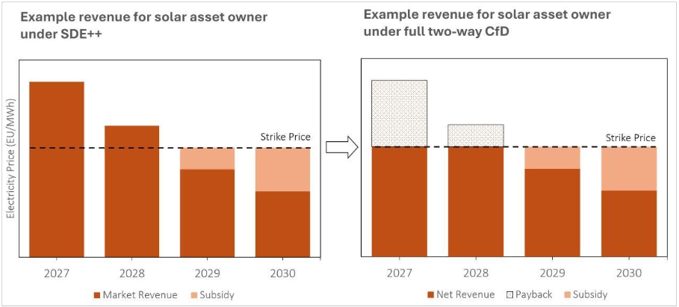

The current SDE++ operates as a one-way CfD, where renewable energy producers are compensated when the market price falls below a predefined base price. However, unlike a two-way CfD, producers under the SDE++ scheme are not required to return excess revenues when market prices exceed the base price.

For an IPP, moving from a one-way CfD to a two-way CfD means that, in addition to receiving compensation for hours when production costs exceed the market price, IPPs will have to pay the government for the hours when the market price exceeds production costs. This would distribute risks between the government and IPPs more evenly and could reduce government expenditure. Looking forward, the relative change in electricity production costs and wholesale prices will determine the impact of the two-way CfD on IPPs. This relationship will be determined by bidding behaviour in the CfD auction (similarly to the current SDE auction), which sets strike prices based on expected capture prices, and market conditions.

In terms of IPP costs, the declining levelized costs of electricity (LCOE) for wind and solar may reduce the need for price support mechanisms. Although Dutch wholesale prices in 2025 have remained roughly similar to 2023, the LCOE of onshore wind and solar is decreasing consistently across Europe. One of the drivers hereof is the declining cost of solar cells. Solar cell prices have fallen by over 90% between 2014 and 2024, and are expected to continue decreasing into 2025.

On the other hand, wholesale price developments and subsequent capture prices, are more difficult to predict. The TNO expects the electricity prices to increase until 2026 and slowly decline until 2030. However, as illustrated by the energy shock following the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine, other geopolitical developments may alter this price-trajectory. The graph below shows an example of a situation whereby electricity prices exceed the set strike price (production cost) and illustrates how two-CfDs could limit the upside potential.

Ultimately, the real effect of two-way CfDs is dependent on wholesale prices and IPPs production cost. Nevertheless, a two-way CfDs is financially more restrictive as it caps earnings in high-price hours.

Strategic Recommendations

As the Netherlands transitions from SDE++ to two-way CfDs and Day-ahead negative price hours become more common, IPPs should consider restructuring their operational and commercial strategies. Reduced subsidy environments and reduced returns on the Day-ahead market force IPPs to find new ways to extract more value from their existing installations.

In this regard, active spot market participation becomes more important, requiring IPPs to move beyond passive price-taking to dynamic trading that capitalizes on intraday price volatility and optimizes revenues more effectively. The route-to-market strategy for IPPs to obtain spot market access is a complex choice between direct trading versus aggregation models. It demands careful evaluation of internal capabilities and risk-tolerance. Direct trading offers maximum control and profit retention but requires investment in trading infrastructure and expertise, while aggregator partnerships provide immediate market access with shared risk and reduced complexity.

Most importantly, IPPs must develop strategies for negative pricing periods in the Day-ahead market, including curtailment steering and multi-market optimization, as negative pricing hours have become more common while subsidy compensation has been reduced.

Simultaneously, IPPs should explore battery storage co-location and demand response participation to create additional revenue streams through grid services, energy arbitrage, and flexibility provision. Participation in congestion management is particularly valuable in the Netherlands, as high levels of Dutch grid congestion create premium pricing opportunities for system balancing services (GOPACS redispatch). These are just a few of the operational changes that IPPs can implement to adapt to these changes.

Conclusion

The Netherlands' renewable energy landscape stands at a critical point. Having transformed from one of Europe's laggards to a leader generating over 50% of electricity from renewables today, the country now faces the complex challenge of managing grid congestion while transitioning away from traditional subsidy mechanisms.

The evolution from SDE++ to two-way Contracts for Difference signals a shift toward market-based renewable energy development. With 458 negative pricing hours recorded in 2024 and over 12,000 companies waiting for a grid connection in 2025, the current system is reaching its operational limits. The estimated annual €10-40 billion cost of grid congestion underscores the urgency of this transition.

For Independent Power Producers, these changes create both significant challenges and opportunities. The reduction in negative-price hour compensation and the introduction of two-way CfDs will compress traditional revenue streams while demanding more sophisticated risk management. However, IPPs that adapt quickly to active market participation, embrace technology integration, and develop flexible business models will find themselves better positioned in an increasingly competitive and dynamic energy market.

The path forward requires immediate action. IPPs cannot afford to wait for policy certainty or perfect market conditions. Those who begin diversifying their market participation strategies, investing in storage and flexibility solutions, and developing direct trading capabilities today will have substantial competitive advantages as the subsidy landscape continues to evolve.